Care and not Conquest

Restoring the History of Gouverneur Morris and Elizabeth Plater

This Essay seeks to peel back the Myth of Gouverneur Morris as “the Rake” among the Founding Fathers further and restore him to the Fullness of who he was: brilliant, neurodivergent, deeply wounded, and longing for Love, Kinship, and Care above all. Not Conquest, as most Biographers so far would have us believe.

In 1780, at just twenty-eight, Morris suffered a Carriage Accident that cost him his left Leg. The medical Trauma of that Moment and the deafening Silence with which he endured it deserves its own Telling elsewhere, but here I want to follow what came after: his Convalescence, and the supposed Romance it inspired.

Except it didn’t.

What remains in Ink and Parchment is not a Trail to Seduction but something much more fragile and far more moving: Kindness, Friendship, Care, and sadly – because it is about Morris – most of all…

Guilt.

I. The Founding of a Rake

His Reputation as a Founder “Playboy” has been built Brick by Brick until the Story stuck. So let me use one of its earliest Cornerstones – the Tale of a Romance with a married Woman who nursed him through Amputation Recovery – to display, just how gradually terminological Inexactitudes can escalate.

It grew through Generations of Biographers who repeated each other’s Assumptions until they began to sound like Fact:

1832

Morris’ first Memoir, written by Jared Sparks with the Backing of Gouverneur’s Widow Ann Morris struck the right Tone. He wrote only that Gouverneur, after losing his Leg, was cared for

“in the family of Mr. Plater” with “every attention, which kindness and sympathy could dictate, and for which he ever after manifested the strongest sense of gratitude.”1

1889

Morris’ Granddaughter Anne Cary Morris published his first “self-authored” Biography, based on the same Materials, including Letters he wrote and Excerpts from the Diaries he kept for himself his whole Life.

She makes no Mention of the Platers at all, but I would like to point out the following Passage:

His letters to his mother were few and unimportant. In 1778 he wrote to her that since he had left Morrisania he had never heard directly from her, and “never had the satisfaction of knowing that of the many letters I have written, you have ever received one.”2

1939

A Century later, Gouverneur’s Great-Granddaughter Beatrix Cary Davenport published the personal Diaries he kept through the French Revolution. Being a gifted and outstanding Writer, she added some ornamental Flourish, setting the first Stone of the Myth.

Nursed in the House of George Plater, (…) by Eliza his wife, gratitude had a halo of romance, leaving a gentle not too insistent melancholy, the armor plating of his heart which wears so thin in Paris.3

1952

In his “The Extraordinary Mr. Morris”, Howard Swiggett quoted Sparks but then reached a Decade forward to anchor his Claim:

Again, this would seem to be all were it not for an entry of unparalleled emotion for Morris in his Diary for May 5, ten years later.4

We will look at said Entry in the next Chapter.

1970

Max Mintz added more Color still:

Elizabeth nursed Morris with more than ordinary kindness,” he wrote, and on Morris’ Side “her attentions aroused more than gratitude.5

2003

Richard Brookhiser leaned heavily on this Scaffolding for the most sensationalist Portrait of Morris in his “The Gentleman Revolutionary”. There he cast him as “the Rake who wrote the Constitution” devoting almost three Pages to the supposed Plater Affair, but without introducing new Sources or Evidence.

Most strikingly he used the Affair to conclude, that the Attentions of a married Woman at his most Vulnerable gave Morris a lasting Sense of Superiority towards other Men. A strange and incomprehensible Judgement, resting more on Projection than Record and reeking of hegemonic masculinity Fantasy.

2004

Melanie Randolph Miller followed, in “Envoy to the Terror”, with her own confident Escalation:

Morris fell in love with the refined and lovely Elizabeth, and she must have been affected as well, for they exchanged obliquely romantic letters long after his departure.6

But no such Sources or Letters are cited.

2024

And still the Myth grows. In her latest Biography, Miller doubled down, describing Eliza as “irresistible” to Morris and insisting she “returned his favor.” To support this, she lifted a single Line from one of Eliza’s Letters – a simple, plaintive Wish that Morris would come visit – and cast it as Evidence of Seduction.

Her claim that Eliza

convinced Gouverneur to cease his inappropriate pursuit7

is more than adrift: it inverts the Truth, distorting the faithful Correspondence of a married Mother of six with Health Issues reliantly asking a Friend to visit.

So much Ink has been spilled imagining Gouverneur’s supposed Passion for Eliza.

But the Picture changes, when we regard what actually flowed from his and their Pens.

II. Facing the Facts — “Thou art then at Peace”

Unfortunately, Gouverneur Morris’s Letters to George and Elizabeth Plater have not survived in permanent Record. The extant Materials consist of the Platers’ Letters to him and Morris’s own Diaries.

While the Platers’ Correspondence provides valuable external Testimony, it is primarily through Morris’s Diaries – his Choice of Quotation, Tone, and rhetorical Register – that his Perspective may be reconstructed and read “between the Lines.”

So from his personal Diary, as transcribed by Beatrix Davenport, here is the Passage that Howard Swiggett seized on as a Lover’s Lament:

May 5, 1790 — London

(…) At five I go to dine with Mr. & Mrs. Beckwith. Mr. R. Penn, who dines here, informs us that they have a Message from the King complaining of the Conduct of Spain in taking two british Ships on the Western Coast of North America. The Idea is that Spain will be frightened into Submission. Just as I am coming away from this Place Mrs. Beckford informs me that Mrs. Plater is dead. I get away as soon as possible that I may not discover Emotions which I cannot conceal. Poor Eliza! My lovely friend; thou art then at Peace and I shall behold thee no more. Never. Never. Never.8

If you know Morris’ writing, nothing here is unusual. This is his Voice — before the Terror, during it, and long after. He leaned constantly on Shakespeare, and most of all on the Kings, whose Words he knew by Heart. Richard III, Henry V, King Lear…

I shall behold thee no more. Never. Never. Never.

These words echo Lear,

Thou'lt come no more. / Never, never, never, never, never. (King Lear, Act 5, Scene 3)

But this is not Romance.

It is filial Grief.

The King is cradling the Body of his dead Daughter Cordelia;

he is mourning his Child.

So why then would Gouverneur Morris choose these exact Words to mourn his “lovely Friend”? The Answer lies in the Plater’s Letters.

The Impossible Lovers

The Plater’s Letters to Gouverneur Morris are Part of the Columbia University Library’s Special Collections within the Gouverneur Morris Papers and have been digitized and provided by the Maryland State Archives. Thank you, dearest Colleagues, for that. I will mark direct Quotes from this Source with a *.

A different Kind of Love

I investigated all Letters to Gouverneur for Traces of Romance or Indications of a Secret Love and found…

nothing.

Instead, they created a Record of a profound 18th Century Friendship of deep Trust, much Fun and Lightness, and an Abundance of Tenderness for each other’s Care… Until Gouverneur ghosted both of them and no longer only Eliza.

But I’m rushing ahead.

The Letters show neatly how George and Eliza Plater became, for a Time, reliable parental Figures, long before they offered their Philadelphia Residence for Gouverneur’s Recovery from the “dreadful Fall”*.

After the Fall

The Myth that Morris, recovering from an Amputation, was in any Way able to entertain a physical Relationship, is untenable. To a modern Reader, it hardly needs to be said — but the Record bears repeating.

George and Gouverneur had planned a Congressional Trip together out of Philadelphia when the Accident struck. The Operation — the Amputation of his left Leg on May 14th, 1780 — was followed by Weeks of Immobility. The first four Weeks of his Recovery, Morris boarded at Mrs. Mary MacKenzie’s House. Her Boarding House was only a few Blocks from the Location of Morris’ carriage accident.9

Within Days from the Accident a concerned George wrote from his Home Estate “Sotterley” in Maryland that Morris’ Doctor had reported him “better the day after we left you.”* George and Eliza had left Philadelphia before Morris was even able to sign his own Name. So the idea that Gouverneur, bedridden with an open Wound and no Painkillers, somehow embarked on a Love Affair during these Months is not only implausible but absurd.

Letters from the Summer confirm Eliza was still in Maryland while Morris could scarcely rise from Bed to a Chair. Only by November was he strong enough to “go abroad”* again, at last leaving his Residence to rejoin Society — too early for his own Good, but true to his seemingly lifelong Refusal of Self-Preservation. He stepped back onto the Philadelphia stage as Ann Willing Bingham’s chosen Master of Ceremonies (a Topic for another “The Art of Seduction”-Essay).

The Platers, meanwhile, remained a distant but steady Presence. Eliza was not a Caretaker in Philadelphia but an absent Friend — her Name as ever constant in George’s Letters, her shared Concern conveyed through her Husband rather than by her own Hand. It was George who checked in on Morris’s Recovery, reported on his Progress, and relayed their shared good Wishes.

Their Bond, formalized in Letters rather than Visits, endured for many Years to come.

Household Errands

George and Gouverneur’s Letters show an Intimacy beyond ordinary Politeness:

They traded Strategy and Gossip, sent each other Poems, Gouverneur checked in on George’s Health frequently and he in Return extended repeated Invitations to his Maryland Estate.

Eliza’s Presence is everywhere in those Letters, mentioned almost ritualistically:

Mrs. P. writes to you*

Mrs. P. threatens to throw a letter towards you*

Even George’s light Teasing of his Wife…

Mrs. P. gives you much trouble, but I believe you don’t think so*

…and my personal Favorite…

the Part of your Letter relative to her I showed her, and don’t doubt but she will give you Pleasure enough as you feel so much in executing her Commands*

… frame Morris not only as a trusted Friend;

the filial Affection and Obligation is palpable.

And so is it in Morris.

Early 1781, just Months after his Accident, he writes to Eliza with the Banter of a Son to a Mother, prompting the Father to respond with

I find you complaining in your Letter to Mrs. P that you don’t hear from me (…) I have nothing worth relating and only take up my pen to convince you that I am not dead, nor have the gout in my thumb.*

So Gouverneur had written to Eliza that her Husband was ghosting him. They were in a more regular Exchange then. But what about?

Things.

Many, many Things.

Shoes, Slippers, Bonnets, gold Thread, Silk... She thanked him for arranging Deliveries, worried about Delays, sent him Measurements of her Feet, and an Apology when she couldn’t complete a promised Purse for want of Materials.

The Line Miller wrenched out of Context to suggest Seduction…

lest I should go too far, as I have once or twice done*

…sits nestled between the most detailed order for Slippers and a dress Bonnet imaginable.

There is not a single Love Note. Just the busy, slightly too insistent Voice of a Woman who appreciated French Fashion, managed a Household with six Children and Social Obligations, gently but a bit cheekily pressing a young Friend to keep her in Supply.

But one, she cared about dearly.

I had the Pleasure of seeing Mr. & Mrs. Griffin on their way to Virginia. Mrs. G. obliging answered me a thousand questions that I wished much to know. She told me your health was very good and that you were very fat, You may easily suppose how happy I was to hear it, take care of yourself my dear Sir and that you may always be well and happy is my constant wish.*

Gouverneur, the friendly Ghost

And here lies the real Story; not hidden Passion, but a familiar and familial Pattern.

George wrote at least a dozen Times urging Morris to come down to Maryland and Eliza echoed him. She longed for a Visit, sometimes slightly reproachful, basically saying “if you wanted, you would”. But Morris never came.

Instead, he carried out each and every of their Favors and Requests from afar, often “forgetting” to bill the Family. What his Biographers cast as Romance reads much more like an Exchange of parental Admonitions, interwoven with Gratitude.

They asked. He obliged.

It is one of the most essential Patterns laced throughout Gouverneur Morris’ Life. He was ever a most obliging Friend to everyone who asked. Friends and Foes alike. This did not set the Platers apart in any way. What did though, was the way they treated him in Return. They thought of him, they considered him.

Family Extension

For Morris the Platers in a parental Role make a lot of Sense, when we consider what he lacked at Home. His Father died when he was young and his Mother rarely answered his Letters, like the Anne Cary Morris quote at the Beginning of the Essay showed to a Point where he asked, if she had even received them.

Eliza and George were the Opposite. They wrote. They noticed. And the Platers seeing Morris as a kind of adopted older Son, also makes Sense considering that they hoped to see him settled. A Topic extremely dear to Gouverneur.

Their Letters are full of References to one Mrs. Richard Lloyd.

Later Beckford, Joanna (née Leigh), who told Morris of Eliza’s Passing, was – in Fact – her Cousin, moving in fashionable Circles.

Eliza nudged Gouverneur with gentle Reminders.

It would add much to my pleasure to see you here with Mrs. Lloyd, you certainly have it in your power and why will you not make your Friends so happy.*

George on the other Hand rather teased him with paternal Winks whenever “the fairest of the fair”* was somewhere in his Orbit.

They watched Gouverneur’s Steps in Philadelphia, passed along Compliments, even relayed that his Poetry had arrived too late. Joanna had already gone before his Verses reached her. But George instantly remedied:

Whenever I play at any Game with a fair woman be assured I always take care to point properly.*

These Moments make clear: they cared about his Future and they noticed when he hesitated. Eliza pressed him, perhaps too boldly at Times, with the Insistence of someone who thought of him as Family, going “Remember the good Times we had with Mrs. Lloyd?” — while George played the Wingman, always name-dropping his young and handsome Bachelor Friend in Philadelphia.

Together, they treated him with the Concern of Parents watching a brilliant but unfortunate Son linger at the Edge of Life’s Stage due to Overwork.

Until it all came crumbling down, in the most familiar Matter.

III. The Bitter End

When the News of Eliza’s Death reached Morris in London, it broke through all his Defenses, shattering the Skepticism and Wariness he had cultivated so carefully in Paris.

“I get away as soon as possible,” he wrote in his Diary, “that I may not discover Emotions which I cannot conceal.”

He was so scared of his own Reaction, because this was not the first Time he learned, that a Mother to him had perished in his Absence.

A Familiar Pain

Sarah Gouverneur Morris passed away on January 15, 1786 in New York, while he was not there.

He canceled a business trip to Baltimore and hastened to New York for the funeral.10

And now, it is May 5th, 1790 and Gouverneur Morris is in London at the House of an old Friend, and somehow he knows in his Heart, the dire News are true. His Shock and Grief are fueled by the terribly familiar Chord Eliza’s Passing struck in him.

He had lost another Mother while he was away.

Eliza had died of Tuberculosis the previous November already.11

He was still stateside then. He could have still seen her, but he never did. And now, he never could again. The Thought filled him with so much Guilt and Regret he put it into his Diary with a Shakespearean Outburst the same Day.

Learning Death

This was not the first Time Morris learned of the Death of a Friend. In Fact this was how News were shared at the Time, and how People learned. They then would write to the affected Party to confirm.

His good Friend Robert R. Livingston had once shared a Rumor, that George Plater had died. Morris immediately, but jocularly checked in with his old Friend, prompting George to reply:

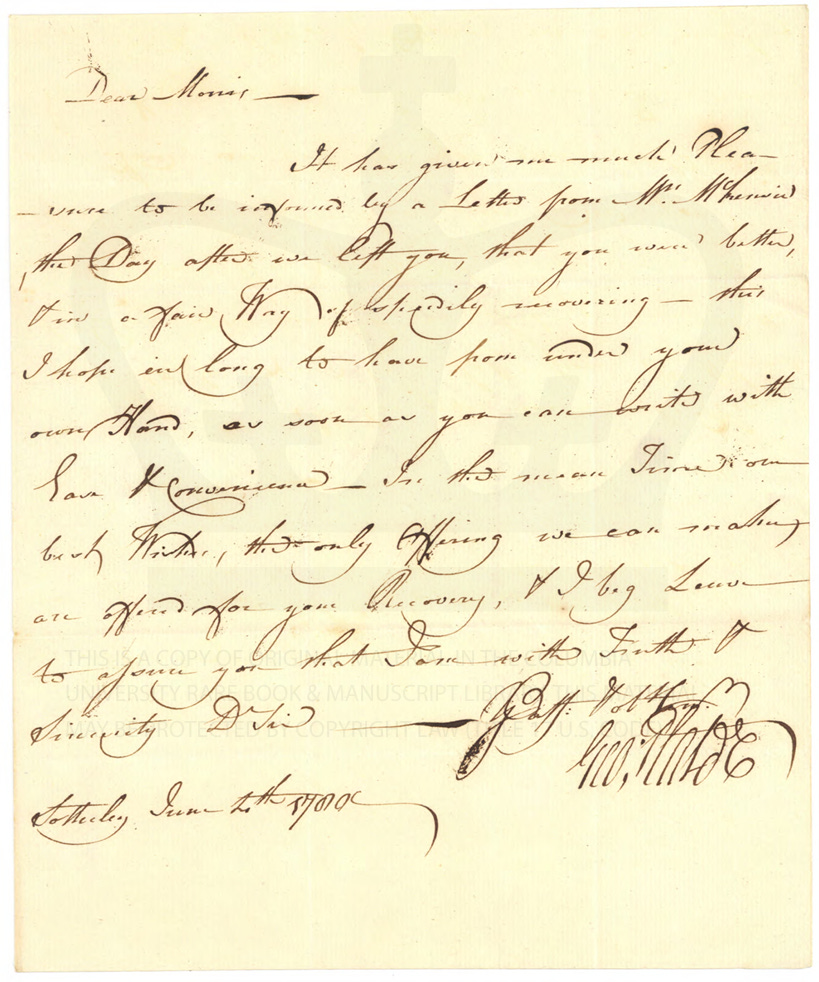

Dear Morris,

I have the Pleasure of two Letters from you, the last of 24th June in which you are pleased to congratulate me upon my Resurrection. I cannot say what induced Mr. [James] to kill me, but this I can say that the Health of my Body is perfect.*

The Timing

This Time unfortunately the Rumor turned out to be true. On the Envelope of a Letter Gouverneur received in London from George Plater in July, the Widower had written the Words:

Mrs. Plater is no more.*

And in the Letter we find another Revelation of what elicited such a strong Reaction of Belief and Shock in Gouverneur, when he heard the sad News three Months earlier incidentally:

Dear Morris,

Your Letter dated Amsterdam March 22nd came safely to my hand, but the person to whom you addressed it is, alas! no more.*

Morris had written to Eliza for the first Time in Years only a couple of Weeks before he learned of her Death.

But transatlantic Post was slow. It could take two, three, even four Months for a Letter to cross between America and Europe. By the time his Words from the Netherlands reached Maryland, she was already gone.

It is very likely that he meant to follow up, to update the Platers after seeing their beloved Mrs. Lloyd, now Beckford, again in London that May. Instead, it was Joanna who told him Eliza was dead. And then, with his own Letter already out in the World, he had no Choice but to wait for George’s Reply.

A Reply that confirmed the sad Loss he had already believed.

The Good News

On the Morning of March 20, Gouverneur Morris sat down to write Letters for the last Time from Amsterdam. He had come from Paris where he was on unofficial Business, and would move on to London the same Weekend, from where he was meant to sail home to New York. His Letters left Amsterdam with him, on March 22.

So why did he take up his Pen to write to Eliza after Years of Silence?

Most likely because he had just met a Sara.

His Diary from the Night before he last sat down to correspond records the Encounter:

Madame Sara seems to have more Understanding than her Sister in Law; she is equally beautiful tho in a different Stile and has an air moins lubrique but her Eyes speak the Language of that Sentiment which warms and melts the Heart …

‘No Pulse but the beat of Delight, no Sound but the Murmur of Joy.’ Heaven knows best, ye fair Daughters of Sion, if ever it will be my Lot to behold you again. All which I can do is to raise some gentle Prepossessions not unfavorable to future Efforts, should Chance ever again place me within that Circle in which you fill so bright a Space.

I find that my Adorations are not illy received by the fair Sara (…)12

Perhaps that was enough. For a Man who bottled up Affection until it burst out in Shakespearean Torrents, even this fleeting Response may have been enough to stir Hope and Memory.

It recalled Eliza’s steady Counsel, her gentle Insistence that he not ruin himself with Work, and the Platers’ half-playful Urging that he seek Companionship. It may have even echoed, the delicate Encouragement Joanna Lloyd had once shown him in Philadelphia.

So when he sat down to write, the Note to Eliza didn’t carry Seduction, but maybe a Trace of bashful Infatuation — “a halo of romance”, as Beatrix Davenport once put it, born not from Conquest but from a Man reminded of how much he longed to be cared for, and to care in Return.

Grief and Guilt

And so, in the bitter End the News of Eliza’s Passing hit with particular Force.

His Grief was doubled. It reopened a Wound couldn’t possibly have healed yet:

his own Mother had died in his Absence without a Farewell.

And now Eliza, his “lovely friend”, the exact same way.

Morris had withdrawn, ghosted the Platers under the Weight of his Work, crossed an Ocean, and then – out of Nowhere – sent them a Letter addressed to Eliza, to talk about Love.

But she was no more.

Ever his own Judge and Hangman, Morris did what he always does;

he turned his Blame inward and wrote.

Like King Lear blamed himself for banishing Cordelia, Morris knew he had let too much slip away, and now would never have the Chance to make it right again.

So if there is a Myth to retire about Morris, it is Conquest;

and if there is a Record to keep in remembering Gouverneur, it is Care.

Post Scriptum: The gentle Poetry of a good Friend

To not end this Essay on the saddest Note on Grief, let me share what Tenderness sprung from George Plater’s Pen in Correspondence with Gouverneur. On January 10, 1779, a particularly hard Winter, he wrote to Gouverneur from Sotterley Hall, excusing himself for not making it back to Philadelphia due to congealed Rivers and Roads — “Another Disappointment which sits heavily upon me and equally affects you is we proposed to send up some Ham Beef Wine etc” he adds most tenderly:

Mrs. P. is now writing by my Side an Epistle to her Friend Mrs. Lee.

She lays down her Pen and swears she grows so fat that she bursts all her Cloathes.

My Observation is that these are bad Times and this a bad Place to get new ones in.I am apt to think that she writes something about you, however it proves that she thinks of her absent Friends and, as a further Proof, desires me to offer her respectful Compliments.

I have almost filled my Paper therefore shall conclude with the following Work.

Oh, May no Cares disturb your peaceful Life,

Your happy House not intermixed with Strife,

And may all your days be bright, your Joys serene,

And Sorrows only by your Foes be seen.Of Your real Friend

Geo. Plater

This four-Line Stanza at the End is the only known Example of an original Poem that appears to be by George himself. It is the most gentle Thing:

The single surviving Verse, tender and protective,

sent to Gouverneur as both Blessing and Benediction.

Sparks, Jared. Life of Gouverneur Morris Vol.I. Gray & Bowen, 1832. p. 223.

Morris, Anne Cary. The Diary and Letters of Gouverneur Morris. Trow’s, 1889. p. 9.

Davenport, Beatrix Cary. A Diary of the French Revolution by Gouverneur Morris 1752-1816 Minister to France during the Terror. George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1939. p. xv.

Swiggett, Howard. The Extraordinary Mr. Morris. Doubleday & Company Inc., 1952. p. 80.

Mintz, Max M. Gouverneur Morris and the American Revolution. University of Oklahoma Press, 1970. p. 141-142.

Miller, Melanie Randolph. Envoy to the Terror: Gouverneur Morris & the French Revolution. Potomac Books, 2004. p. 5.

Miller, Melanie Randolph. An Incautious Man - The Life of Gouverneur Morris. Regnery Gateway, 2024. p. 46-47.

Davenport, ibid.

About Beckwith/Beckford; Ms Davenport states, “Monotony when writing names of persons was not yet the fashion; with Morris, phonetic spelling at first hearing gradually hardened to some accepted form.” p. IX)

Levinson, Adam. “Gouverneur Morris: Amputation and Recovery”. statutesandstories.com, 2023. Accessed October 22, 2025.

Mintz, Max M. ibid. p. 172.

Kirschke, James. Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, And Man of the World. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. p. 119.

Davenport, ibid. p. 452.