We the People, He the Mind

Gouverneur Morris and the Burden of Genius

“I am a busy Man tho as heretofore a pleasurable one.”

Gouverneur Morris to John Jay, 29 April 1778

Gouverneur Morris was not the carefree “Rake” that History and his 20th and 21st Century Biographers have made him out to be, but a neurodivergent Polymath living on the Brink of Exhaustion. A Man who coped with relentless Overwork, social Misunderstanding, and Isolation by Writing, Reasoning, and desperately Rebuilding the World around him.

What History mistook for Pleasure was often Survival.

And what looked like Restlessness was his Inability of falling still.

Across a Lifetime spent drafting Constitutions, rebuilding Economies, and organizing Chaos into Order, Morris poured every Ounce of Thought into keeping the Systems around him alive for the Good of the People — until, at the very End, the same Impulse that built the Republic turned inward, as he tried to repair the only System he had never been quite able to regulate:

His own Body and Mind.

I. The Libertine Freemind

For two Centuries, Gouverneur Morris has been flattened into a Libertine Caricature — “the Rake among the Founders,” and a man of “Talents and Foibles”1 whom his Friends supposedly teased for his Conquests. Brookhiser quotes these Fragments eagerly, even reviving Swiggett’s apocryphal Letters to make Morris sound like a restless Libertine before the Accident in 1780.

But the Image of the Man with too many Women

obscures the Truth of the Man with too many Burdens.

In a Letter replying to Livingston’s Joke about his supposed leisurely Activities in New York, Gouverneur confessed, “I have suffered much in my short Life from being thought happier than I was.”2

Beneath the Myth of Indulgence lies the Reality of Exhaustion:

a Mind that burned too bright, overworked, and achingly alone.

II. A Mind in Overdrive: The 1778–1787 Testimonies

In another Letter Gouverneur wrote to Livingston in 1778:

(…) the every Day Minutiae are infinite. From Sunday Morning to Saturday Night I have no Exercise unless to walk from where I now sit about fifty Yards to Congress and to return. My Constitution sinks under this and the Heat of this pestiferous Climate. Duer talks daily of going hence. We have nobody else here so that if I quit the State will be unrepresented. Can I come to you? If there be a Practicability of it with any Kind of Consistency I will take half a dozen Shirts and ride Post to meet you. Oh that a Heart so disposed as mine is to social Delights should be worn and torn to Pieces with public Anxieties.

It is a striking Self-Portrait, eliminating himself as a Man of Leisure, painting a Picture of relentless Motion without Movement — trapped in administrative Overdrive.

For someone who delighted in Riding, Walking, Gardening, and Fishing, the quiet Admission that he could now only move between his Desk and Congress Chamber really captures the quiet Desperation: the forced Standstill of a Freemind burned out by Duty.

In 1778 Gouverneur Morris was twenty-six. One of the Youngest in Continental Congress, already carrying what older Men would have shared among many. The Weight that would crush most People he took as ordinary Obligation, mistaking Precocity for Capacity.

It is a famously neurodivergent Trap: The Hyperfocus, the Insomnia, the Inability to rest — all bound to a Conviction that if he stepped away, someone else would do it worse. His Mind makes it his Responsibility, and it consumes him.

That’s why he sends out a Plea to his older Friend:

“Can I come to you? Please give me a practical Reason and I will.”

Even his Wish for Rest must take the Form of Procedure.

He was a grown Man not needing to answer to anyone but himself. Yet he cannot simply leave; he must make it official, rational, defensible to his own Head.

His Body is begging for Reprieve, but his Mind will only permit it as sanctioned Duty. What we now recognize as a neurodivergent Cycle of Overstimulation and Self-Punishment was, for him, simply Life. His Heart longed for Company and Joy, yet was constantly crushed by the Weight of public Duty.

Solitude became both the Cost and the Symptom of his Brilliance.

And he was painfully aware of it.

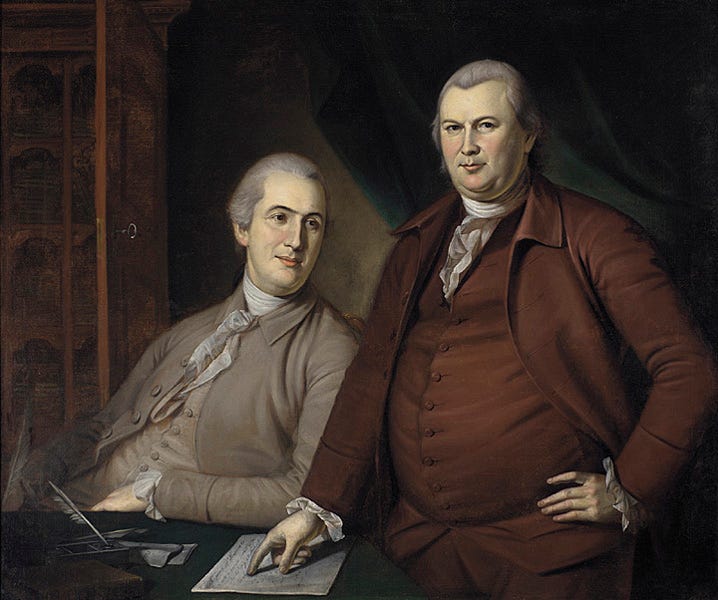

Only a few Months later in October he wrote again — this Time to another much older Friend, Robert Morris:

That I am not a punctual Correspondent must be attributed to Distractions arising from an Attention to Business of so many different Kinds, that your poor Friend hath but little in him of the gay Lothario.

The supposed “Rake among the Founders” — whom later Biographers cast as a Man “daily employed in making Oblations to Venus”3 — makes Fun of his own Image, which he cannot live up to because he is too exhausted to even write a Letter.

As I have pointed out in previous Essays: when Morris quotes Literature, Things are serious. Lothario is the main Character in Nicholas Rowe’s The Fair Penitent (1703); an archetypal and cold-hearted Libertine who seduces, betrays, and destroys Women—and thus became the proverbial Blueprint for the Womanizer in the 18th century.

These two Letters alone, however, reveal instead a self-reflective Man who is fraying at every Seam. His Observers saw only the Glitter, never the Wear and Tear of a Freemind that ran hotter than his Century could understand.

III. Contemporaries and Caricatures: A misread Genius

To his Peers at the Time, Gouverneur Morris was a Paradox.

John Adams called him très légère — light, superficial, too witty to be serious.

General Nathanael Greene thought he had “more of Genius than Judgment.”

Francisco de Miranda saw in him “the lively Intellect of the Town, (…) more Ostentation, Audacity, and Tinsel than real Value.”

To Men like these, bred on Predictability and Restraint, Morris’s Quicksilver Mind must have seemed erratic — too sharp, too bright, too fast.

His Energy spilled past Convention.

William Pierce who sketched the Members of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 wrote:

He winds through all the Mazes of Rhetoric, and throws around him such a Glare that he charms, captivates, and leads away the Senses of all who hear him. With an infinite Stretch of Fancy he brings to View Things when he is engaged in deep Argumentation, that render all the Labor of Reasoning easy and pleasing.

But with all these Powers he is fickle and inconstant,—never pursuing one Train of Thinking,—nor ever regular. He has gone through a very extensive Course of Reading, and is acquainted with all the Sciences.

No Man has more Wit,—nor can any one engage the Attention more than Mr. Morris.

For many of his Contemporaries, Morris was a sparkling Mind but not a consistent Thinker—a Firework without Focus.

Even George Washington, who deeply valued and made use of the Gouverneur’s Intellect, recorded the same Contradiction that would haunt Morris for Life:

a Mind admired, in a Body misread.

“His imagination sometimes runs ahead of his judgment,” Washington noted in his personal Diary, “and his manners before he is known — and where known — are oftentimes disgusting.”

In the Language of the Time, “disgusting” meant socially offensive, not depraved; Washington saw how Gouverneur’s Humor, Wit, and uninhibited Candor offended genteel Sensibilities. He was too blunt, too funny, too physical, too real for the polished Restraint expected in elite Company.

In short: Gouverneur was socially noncompliant — neurodivergent, we might say now — and Washington, ever a Stronghold and keen Observer of Decorum, noticed how that clashed with public Perception. Morris’s Wit and Ease unsettled.

Yet Washington saw the Truth others missed: that these “unfavorable Opinions” were of Society’s Making, not Morris’s. Judgment, “which he did not merit.”

In a World that had no Vocabulary for Neurodivergence, Gouverneur Morris lived on a Frequency most People couldn’t hear — mistaking the Sound for Noise.

➜ What others considered Arrogance was in fact Overheating —

the Speed of Thought of a Mind running ahead of its Time.

IV. Writing as Self-Regulation

Morris always wrote himself out of a mental Health Crisis.

Each Turn in his Life — from Law to Finance, from Diplomacy to Engineering — his Movements as a Universal Genius were the coping Mechanism of a Mind that could not rest.

When the New York Legislature voted him out of Congress in 1779, he was devastated. After Years of dedicated Service, for which we just learned he gave Himself up, and during which he reformed Supply Lines, drafted Military Codes, secured the Survival of freezing and starving Soldiers at Valley Forge etc. etc. he was cast aside by political Rivals.

So he did what he always does: He left.

He left Congress and his Hometown New York, reinvented himself as a Pennsylvanian Citizen, reluctantly returned to the Legal Profession to earn a Living, and, in the Middle of his Despair, began writing Essays on the Country’s Finances and published them in the Pennsylvania Packet, signed “An American”.

These Essays — dry, analytical, but incredibly visionary, realistic, and humane — were not the Work of a detached Economist, but of a Man trying to regain mental Equilibrium. He dissected national Debt and Currency as if order on Paper might restore Order in his own Mind. Every Theory of fiscal Structure is also a Theory of Self-Control.

For a neurodivergent Mind like his, the Impulse to fix the System comes from Necessity not Vanity. It is an old and infamous Survival Strategy: when the World felt misaligned, he sought to realign it — to make external Order compensate for an internal Overload. And as with many such Minds, his Sense of Justice was exaggerated, almost painfully sensitive:

If Good could not happen to him, he was determined to make it happen through him — for the People, for the Country he had helped wrest from Monarchy, for anyone who might live easier under fairer Conditions in the New World.

Across his Life, this Pattern repeats with mathematical Precision.

When overworked, he rebuilt Systems.

When rejected, he wrote Frameworks.

When heartbroken, he documented.

His Mind, constantly on the Verge of Collapse, found Stability only in Design;

Law, Finance, Diplomacy, Street Grid and Construction Planning —

each less of a Career than a Form of Therapy.

➜ The Order of the World became his Means of Self-Control —

an endless Attempt to repair the Outside in order to maintain the Inside.

V. The Unwritten Life

By 1809, Gouverneur Morris had returned to America after ten Years abroad serving as a Merchant, then Diplomat, at 57 years old. He returned as a Man who had built Systems for everyone but himself.

In his Letter to the young Historian Jared Sparks, who would become his first Biographer, Morris apologizes for having “no Notes or Memorandums” of his Relative’s Service during the Revolution — but the Apology is more than administrative;

it is existential.

I have no Notes or Memorandums of what passed during the War. I led then the most laborious Life, which can be imagined.

This you will readily suppose to have been the Case, when I was engaged with my departed Friend, Robert Morris, in the Office of Finance. But what you will not so readily suppose is, that I was still more harassed while a Member of Congress. Not to mention the Attendance from eleven to four in the House, which was common to all, and the Appointment to special Committees, of which I had a full Share, I was at the same time Chairman, and of course did the Business, of three standing Committees, viz. on the Commissary’s, Quartermaster’s, and Medical Departments.

You must not imagine, that the Members of these Committees took any Charge or Burden of the Affairs. Necessity, preserving the democratical Forms, assumed the monarchical Substance of Business.

The Chairman received and answered all Letters and other Applications, took every Step which he deemed essential, prepared Reports, gave Orders, and the like, and merely took the Members of a Committee into a Chamber, and for the Form’s Sake made the needful Communications, and received their Approbation, which was given of Course.

I was moreover obliged to labor occasionally in my Profession, as my Wages were insufficient for my Support.

I would not trouble you, my dear Sir, with this Abstract of my Situation, if it did not appear necessary to show you why, having so many near Relations of my own Blood in our Armies, I kept no Notes of their Services.

Nay I could not furnish any tolerable Memorandum of my own Existence during that eventful Period of American History.

Once again, he had been asked to recount the Lives of Others — as he had publicly and so eloquently done for Washington and Hamilton in their Deaths. But this Time, the Request struck closer: it concerned his own Kin — his Parents, his Brothers, his Uncles, his Cousins. The People who had not, in Truth, ever cared to recount his.

Perhaps that is what finally compelled Gouverneur Morris to turn the Lens inward. He had navigated the History of his Friends and fellow Statemen with Composure upon their Loss, but the Thought of his own Family — of a Mother who sided with the Enemy, of Brothers twice his Age who sued and dismissed him, of a Home that offered no Shelter — tore through the Discipline of public Tone.

They asked how his Blood served in the War and not he.

And so it was to Sparks that he finally answered out of his Skin as the polished Orator and Diplomat, but in his own Body of the overworked Son who had built a Life out of Self-Preservation.

Fighting the Enemy and defending the Country with the Pen not a Sword

in his early Twenties.

What he outlines here is a Pattern painfully familiar even today: the endless Labor of those who keep Institutions running while rarely holding Power themselves. It is the quiet Exhaustion of being indispensable yet invisible — a State modern Readers, and especially Women in Staff Roles, will recognize instantly.

The Labor never ends; only the Credit does.

So he lists his Duties with mechanical Precision: the Hours in Congress, the Committees, the endless Letters, the Medical and Commissary Departments, the financial Oversight, even the Need to moonlight, and practice Law on the Side to afford a Living.

The Tone is factual, but what leaks through is Fatigue.

A Lifetime’s Worth of it.

And beneath his calm Explanation lies the quiet Reckoning of a Man who had been overburdened too early and too long and left alone to survive it. The Absence of Records becomes its own Record — Proof that he had given Everything away in the Service of everyone else.

Most people only recognize such Exhaustion after the Fact. But Morris saw it while it was happening. His letters show the Clarity of a Man who understood his own Decline yet kept moving through it — documenting, reasoning, enduring.

I have shown you the Traces here, the Exhaustion already visible — the sleepless Weeks, the Paperwork, the Self-Reproach for being “no punctual Correspondent,” the aching Confession that he was thought “happier than I was.”

Every surviving Letter becomes a Fragment supporting the Truth of the very Memorandum he claims not to possess:

a dispersed Diary of Endurance.

“I could not furnish any tolerable memorandum of my own existence,” he wrote — or, in the harsher Version transcribed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s History Department Archive:

“I am perhaps the most ignorant man alive of what concerns them.”4

It is a Confession stripped of Rhetoric.

The Man who drafted the Constitution, who gave America its grammatical Center in We the People of the United States, admits that he has no narrative Center of his own.

He could design a Government, but not rest.

He could organize Armies, but not his Emotions.

He could structure a Nation, but not sustain himself.

All his Life, Morris had been the Architecture — but never the Inhabitant.

VI. The Architecture of Survival

Gouverneur Morris’s true Legacy lies not in his Charm, nor in the Vices that Biographers loved to magnify, but in his Endurance. In his Refusal to collapse beneath the Weight of his own Mind.

The same Impulse that drove him to Exhaustion in 1780, that Need to fix, to mend, to unclog Systems, make them work, is the One that would lead him to try to heal himself in 1816.

His final Project of Improvement was not political, but existential: a Man under Pressure attempting to repair his own Body; the System Carrier of his Mind.

He lived, always, on the constant Edge of a Breakdown — saving others to save Himself — yet every Reinvention, every new Framework for Survival, only proved that his Mind could create anything but Rest.

His Letters, his Essays, his meticulous Reports, even the Diary that never stopped recording, were never primarily Works for the Public, but rather a Framework he erected to create Order where Chaos threatened. Outwardly, it appeared stable, but inwardly it lacked the Support to keep the Structure from collapsing.

It is tempting to call him a tragic Figure, but that would miss the quiet Triumph at his Core and diminish what he has done for the World. Because for all the Exhaustion, all the Self-Mockery, and all the Labor, he remained in Motion — saving Lives, improving the World, trying to keeping People from hurting each other.

Gouverneur Morris was a Man who refused Inertia and never stopped reaching for the better World he imagined. And even if that Refusal was not entirely voluntary — if his Mind was both built and burdened to keep moving — I believe that his Doing, Thinking, and Creating were deserving of Grace.

➜ He did not leave behind a Record of Ease.

He left behind a Record of Effort — the Architecture of Survival itself.

And here, across two Centuries, I recognize him too well. Too young, too capable, too practical to be spared — surrounded by older Men he was useful to, carrying what they would not, unpraised for surviving what should never have been demanded.

The World still calls it Talent. Gifted. Genius.

But Brilliance without Protection is a Kind of Cruelty.

And that is the Burden of Endurance.

Brookhiser, Richard. Gentleman Revolutionary - The Rake who wrote the Constitution. Free Press, 2003. p. 59.

ibid, p. 60.

ibid.

This, and all other Letters quoted in this Essay: Founders of the American Republic: Documentary History Archive, University of Wisconsin–Madison, archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/fotm_0214_gouverneur_morris.pdf. Accessed 5 Oct. 2025.